When Assessment Becomes a Conversation

What we’re learning from piloting Viva as an oral assessment tool

This year, we began piloting Viva, an oral assessment platform developed by the team at InitialView and used by Caltech as part of its admissions process. We are the first high school in the country to test it in a learning context. That connection to higher education is an important part of the story—but not because of prestige. It’s because we’re asking the same question: how do we see student understanding more clearly?

Seeing Thinking, Not Just Artifacts

What we’re really interested in exploring is how Viva enables a more direct, spoken form of assessment—at scale. This isn’t about replacing written work, but about revealing layers of understanding that written artifacts alone often fail to show.

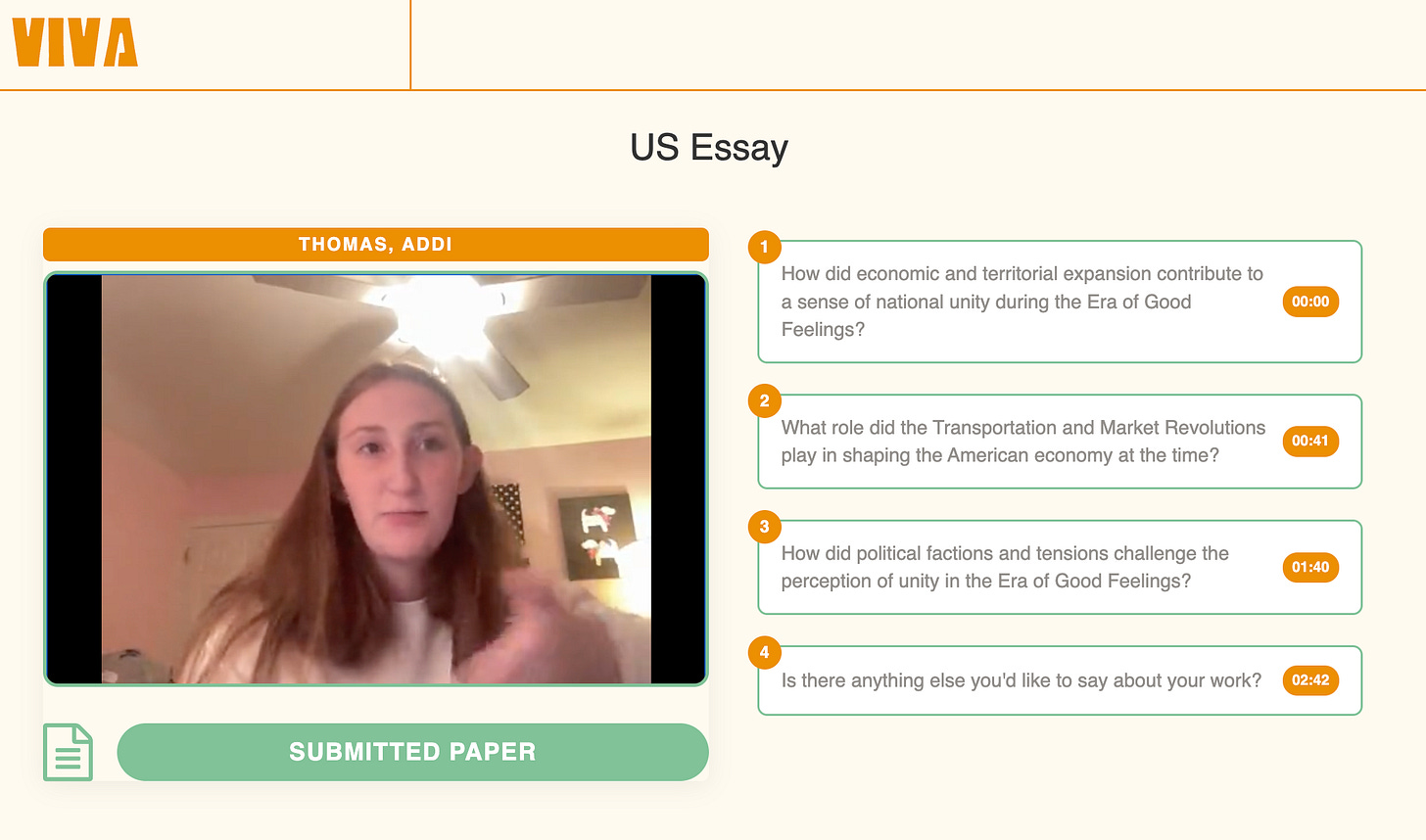

In practice, students upload their written work, and the platform uses an LLM to generate a small set of tailored questions—currently four, though that will likely evolve—based directly on what they’ve produced. Students then respond in real time, recording brief oral explanations through their computer’s camera, using their own writing as the starting point for explanation. The result is a clearer view of how well ideas are understood, not just how well they’re presented.

What Happens When the Camera Turns On

One of the most striking early observations from the pilot has been how students respond once the camera turns on and the questioning begins. There’s a noticeable shift in posture and attention: students become more alert, more present, and more engaged with their own thinking. The format can feel slightly intimidating at first—yet that discomfort is part of what makes it valuable. It asks students to take ownership of their ideas in real time, rather than relying on distance, polish, or revision. And in the AI era, this sort of just-in-time conversational competency has real value.

Importantly, this is also why we see Viva as something to practice with students, not simply deploy. Like any meaningful form of performance, oral explanation improves with familiarity. The goal isn’t to catch students off guard, but to help them grow more fluent in explaining what they know and how they know it.

Oral Assessment, Tradition, and the Problem of Scale

This experience echoes a point Daniel Willingham has recently made about the value of oral exams in college teaching.1 Oral assessments surface whether students can explain, connect, and reason with ideas—not just reproduce them. They make understanding visible in ways written work often cannot.

In higher education, this kind of assessment is feasible precisely because of teaching schedules. College instructors typically work with fewer sections, making time-intensive oral exams possible. In high schools, that same approach has largely remained aspirational. Teaching four or more classes, often with dozens of students per section, makes sustained oral assessment difficult to implement with any regularity.

What interests us about Viva is that it meaningfully changes this constraint. By structuring and scaling the questioning process, it makes oral assessment possible in contexts where it has traditionally been out of reach—not as a replacement for teacher judgment, but as a way to make those judgments more informed and more feasible.

AI, Integrity, and a Pedagogical Turn

It would be disingenuous not to acknowledge that many educators initially approach tools like Viva through the lens of academic integrity. In an environment where generative AI can accelerate the production of polished written work, it’s reasonable for teachers to look for assessment designs that make student understanding harder to outsource.

What’s been notable in our pilot, however, is how quickly that framing gives way to something more pedagogically interesting. Viva doesn’t function primarily as a safeguard; it functions more as a speed bump to generating one’s work with AI assistance. Because students must explain ideas aloud, in real time, and in response to questions generated directly from their own writing, the assessment shifts from product to process. Students can still prepare thoughtfully—but they can’t remain distant from the thinking itself.

In that sense, the value of oral assessment isn’t that it “catches” misuse of AI. It’s that it changes the cognitive demands of the task. Explanation, transfer, and reasoning become unavoidable. The tool nudges students toward deeper engagement with their own work, and teachers toward clearer insight into what students actually understand.

Formative Use, Accommodations, and the Edges We’re Still Working Through

For now, we’re intentionally keeping this pilot in the formative space. That decision is partly practical—we’re learning how students respond, what the platform reliably surfaces, and where it adds value—but it’s also ethical. Oral assessment introduces real questions about access and fairness: how it intersects with anxiety, language processing, neurodiversity, and the accommodations many students understandably rely on.

Some of the thorniest details are also the most important. If a student receives extended time, what does “extended time” mean in an oral format? If a student benefits from breaks, reduced distraction, or prompts repeated or rephrased, how do we build those supports in without warping the assessment itself? Those aren’t reasons to avoid oral assessment—they’re reasons to pilot it carefully, gather feedback, and define norms before we attach higher stakes.

In other words, we’re not treating Viva as a finished solution. We’re treating it as a design space: a chance to figure out how oral explanation can become a fair, repeatable part of how students demonstrate understanding.

Where This Leaves Us

We don’t see this pilot as a verdict on assessment, nor as a blueprint to be replicated wholesale. We see it as a careful investigation—one that helps us ask better questions about how students demonstrate understanding, and how schools might widen the range of signals they take seriously.

Viva has given us a practical way to reintroduce oral explanation into learning at a scale that high schools have historically struggled to manage. Just as importantly, it has prompted productive conversations among teachers and students about ownership, preparation, and what it really means to understand one’s work. Those conversations, more than any single tool, are the point.

We’ll continue to refine this pilot, share what we’re learning, and remain honest about its limits as well as its promise. If you’re curious, skeptical, or simply wondering how something like this might fit in your own context, we’d welcome the conversation. Reach out—we’re learning in public, and better questions tend to emerge when more people are part of the inquiry.

It’s worth noting that the experience we’re describing here is not identical to the oral exams Dan outlines. In his teaching, oral assessment often takes the form of a live dialogue—reading through student work together, responding to emotional cues in real time, and adjusting questions dynamically. Viva does not replicate that level of human interaction. What it does offer, however, is a “pretty good” approximation at a scale that makes oral assessment feasible in high school contexts. For us, that tradeoff is worth investigating—without letting the perfect become the enemy of meaningful improvement.