We’re often asked the question “What are you working on?” here in the Center for Teaching and Learning. It’s a fun question to answer. It allows us to mine the depths of the work that folks in the Center focus on, but in reality it oftentimes fails to capture all of the things we’re doing. We have dedicated programming and a slate of offerings that make up our day-to-day work. So too do we have medium and longer term projects that simmer in the background, bubbling up periodically throughout the school year and beyond. However, as one of the few dedicated centers for teaching and learning in K-12 independent schools (and indeed one that is well-established) it feels as though we have the capacity, perhaps even the responsibility, to expand our scope and reach.

Right Place, Right Time

Inspiration and creativity can often strike at unexpected times. Such was the case when I was recently in the audience for Dr. David Daniel's talk on ‘Useable Knowledge: Making Research Relevant to Those Who Actually Teach’ at this fall’s Learning and the Brain conference. Daniel, in only the way that he can, playfully poked fun at education’s obsession with evidence-informed practice, given that much of this research is generated outside of classroom settings.1 We are big fans of educational research and evidence informed practice here in the CTL. But we are also cognizant of (and frequently grapple with) making research relevant and allowing teachers to understand its significance in their respective areas. The early portion of Daniel’s talk recognized and gave credence to this tension—but it was the middle and end that really caught my attention.

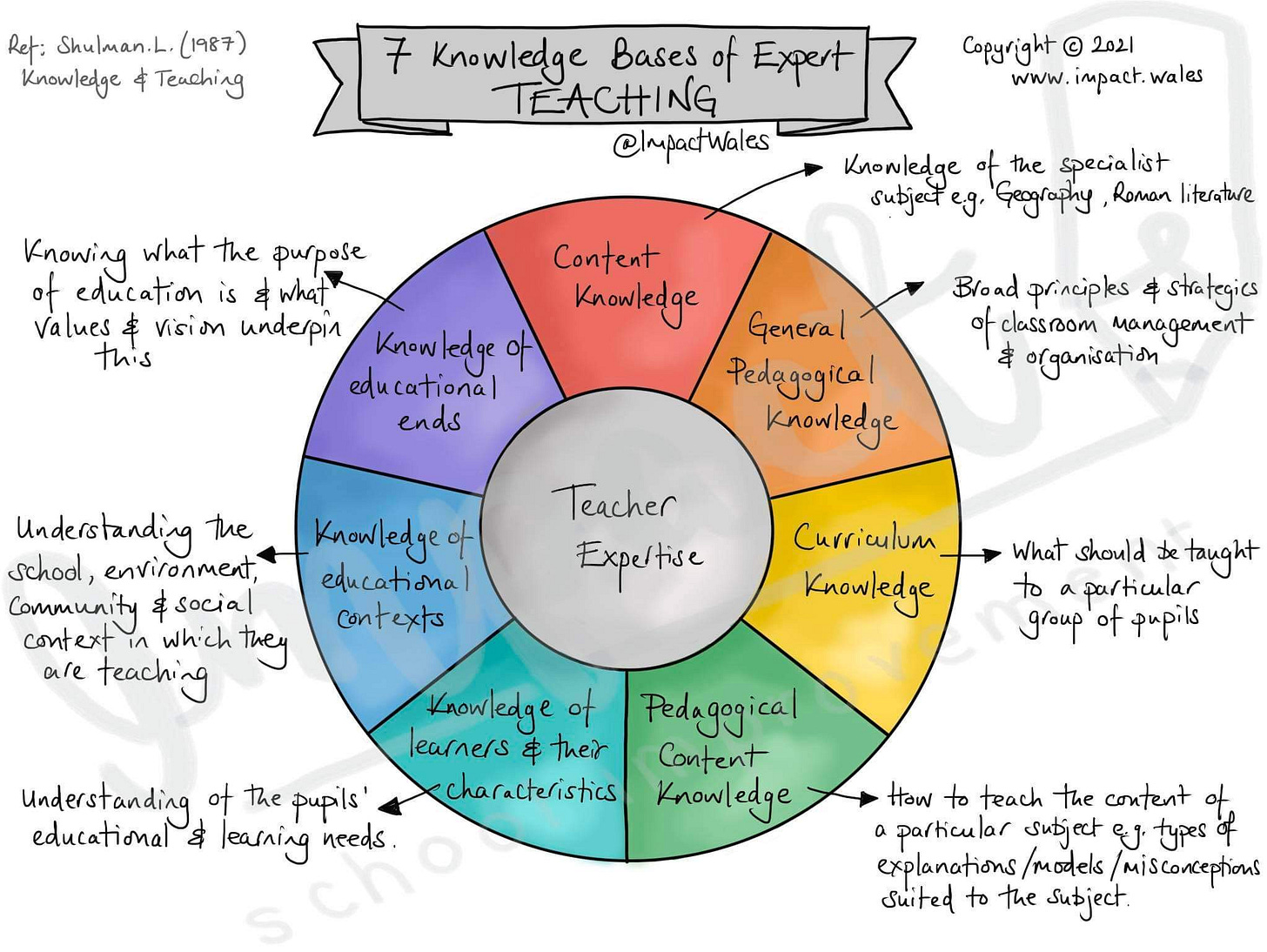

Pointing out the discrepancy between work done in laboratory settings and work done in the classroom, Daniel nonetheless advocated for the development of what he called a “Science of Teaching.” He emphasized the importance of teacher experience and expertise in local contexts. He encouraged teachers to engage in a kind of research in their own settings and to begin to share this research. At one point mid-presentation, I quickly penned a note to a friend seated next to me, writing, “There is a Scholarship of Teaching & Learning (SoTL) that seeks to do this in higher ed—this approach informs some of our work at EA. We’re going to lean way more into this soon.” Daniel’s very next slide explicitly referenced the work of the SoTL community in higher education. Many of his remaining slides further articulated the need for a SoTL-esque approach in K-12 settings. This work has already begun here at EA’s CTL. While it is very much in the nascent stages, a SoTL mindset nonetheless pervades much of our pre-existing programming. Our Hirtle Grants for Inclusivity—aimed at advancing faculty expertise in inclusive teaching—promote reflective teaching practices throughout the entirety of this yearlong cohort.2 We routinely espouse the work of Lee Shulman, an early founder of the SoTL movement, given his emphasis on the importance of teacher knowledge in things such as context, of learners, and of educational ends in their particular setting.3 And we’ve begun to establish a cohort of teacher practitioners in this work as a kind of early-stage SoTL Expedition Team.

Answering the Call

Daniel’s talk was a clarion call for K-12 education to begin taking ownership of this work. Doing this alone, amidst other daily responsibilities, is nearly impossible for individual educators. However, with the resources at CTL, we are poised to support teachers at EA and beyond in this paradigm shift. That shift, one predicated upon transitioning from the mere implementation of research-informed practice in the classroom, to understanding the teaching itself as a form of research, sits at the heart of our work ahead.4 Our focus will always start with our teachers here at EA, but that focus needn’t (and won’t) end there. We have a commitment to sharing our learning with K-12 learning communities throughout the country and beyond. We’ve started The Beacon as one way of sharing our learning beyond our campus. So too will we continue to expand on our monthly virtual Leaders of Teaching and Learning gatherings and annual, in-person Transforming Teaching Summer Collaborative.5 A historian by trade, I am also drawn to EA’s motto, Esse Quam Videri—or, “To be, rather than to seem” as a form of inspiration. How might we illuminate what good teaching is, rather than what it seems to be? And in doing so, how might this also lead to growth of teachers and teaching, and improved learning for our students?

A number of frameworks exist around what the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning entails. We are partial to Peter Felten’s work in this regard, but there are no doubt other models and aspects to consider. Indeed, the development of this approach here at EA will likely take on its own characteristics as the work evolves in the weeks, months, and years ahead. It will often be messy. But in the messiness and uncertainty, there will undoubtedly be learning. And we will share that learning along the way. We will be diligent about considering evidence and proof. We will wrestle with the complexities of operational definition and methodology. And we will look to promote what Daniel calls “promising practices” as they arise, with the hopes that others might carry these forth in their own contexts.

With the utmost humility we seek to answer Daniel’s call and to ignite this movement toward a kind of “Science of Teaching” in K-12 contexts. Leveraging our outstanding faculty here at The Episcopal Academy, the work of so many excellent scholars in the SoTL community, and our network of outstanding peers and colleagues at institutions throughout the country and the world, we look forward to the work and the learning ahead.

Providing teachers with the tools and information needed to evaluate and implement promising principles is the core of what would make a Science of Teaching an inspirational source of truly innovative teaching and learning practice and the context to enrich theories and models of learning and development. This, we argue, can more effectively happen with attention to complexity within an ecological framework. In this way, a science of teaching would also become a science for teaching.—Daniel & De Bruyckere, (2021).

Please do not think he was fundamentally rejecting research-informed practice. This was very much not the case. Instead, he was challenging teachers and schools to consider the nature of this research and just how practical (or impractical) much of it is in their particular contexts.

While ‘Reflective Teaching’ is an element of SoTL work, it does not capture it in its entirety. But it is an important step along the way. Remember, we’re nascent. These are seeds. (Also, we’re presenting on this program at this year’s Carney Sandoe DEIB Forum in Philadelphia on January 26).

This post is not intended to be a history or literature review of the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning as it has existed in higher education. Folks such as, but not limited to, Shulman (who undertook work in this realm while leading the Carnegie Foundation in the early 90’s) along with Randy Bass have espoused the merits of a SoTL approach for some time. We are not suggesting that this approach is new or novel. However, applying SoTL principles in K-12 contexts does offer some possibly interesting paths forward. For more, from Bass, see here—The Scholarship of Teaching: What’s the Problem (1999)

Concerns sometimes arise here for folks, who grow wary about teachers trying things in the classroom and viewing it as a kind of lab setting. This is an understandable concern, albeit one that takes on a different tone when considered deeply. In reality, everything that a teacher does in the classroom is a kind of hypothesis geared towards promoting student learning. What this approach allows for, is both an attempt at improved teaching, and a consideration of what worked, how we know it worked, and what others might learn from the practice.

Want to know more? Reach out to us at ctl@episcopalacademy.org